Join me on this Saturday for an artist talk at CONTACT →

SALAM FROM NIAGARA FALLS takes up first- and second-generation Afghan and Iranian home-making in the context of ongoing settler colonialism on Turtle Island. Family photographs taken at Niagara Falls are a staple in many migrant and refugee homes, often evoking newfound relationships to belonging in Canada. Artists refute the nostalgia associated with Canada as “a nation of immigrants,” drawing from and digitally manipulating archives to share experiences with migration, displacement, and settlement. Curated by Mitra Fakhrashrafi.

Shelby Lisk (Shelby Lisk Photography) is an artist, writer and photographer, born and raised in Belleville, close to her roots of Kenhtè:ke (Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory). Shelby's work responds to the colonial history of landscape painting, land ownership, and more broadly the forms of knowledge that are more easily taken for granted as truth. In drawing from her poetry and photo-based practice, Shelby will extend a discussion on colonial landscapes, nostalgia and the possibilities of imagining multitudes of perspectives, stories, and histories. Talk will be in English but Q&A period is open to questions in English, Farsi + Dari. Free tea + refreshments on site.

Thanks to everyone who came out for A room of One's Own - Opening reception

Lyndsay and Will's winter wedding

A winter wedding in Calabogie, with an outdoor ceremony

Read Moreexhibition announcement: keró:roks tsi naho’ténhson sewake’nikonhrhèn:’en

Please join me for the opening of my first solo exhibition, at Modern Fuel in Kingston, Ont. The show will run from September 4 - October 20th, with the opening reception on September 14 from 6-8pm. The work in this show centres around my relationship to my maternal grandmother and to the land in Tyendinaga. As well as blood memory and family ties. Christine Negus' exhibition 'things you can't make maps out of..' will be showing at the same time

Below is from my artist statement for the show

Keró:roks tsi naho’ténhson sewake’nikonhrhèn:’en translates to I am gathering all of the things I had forgotten, in English. This show centres around my connection to the water and land of Tyendinaga and my maternal, Mohawk grandmother. Each piece in the show is a part of remembering. It’s like waking up from a long dream and finding who you’ve always been. The land, the water and my grandmother: each a piece of remembering.

I thought if I spent enough time with water I could access some of the knowledge it has of my ancestors and tell me secrets of the past: remember my great aunt paddling along it, back and forth on her back. Remember our ancestors landing here, remember my mom’s giggles as a child, held tightly in its waves. Remember canoes gently gliding, kissing its surface. I thought it could help me remember these things that I had forgotten but also I could remind her of how much we love and care for her. That we don’t just want to use her, we want to spend intimate moments talking quietly in the dark, breathing close to her, blowing cool air across her surface. I think of her simultaneously like I would my child and my aging grandmother. Rub her head when she’s afraid and listen to her wisdom and bring her tea in exchange for her stories. She is where we come from and where we're going.

video still from Akshótha, 2015

Water feels like my connection to the territory of Tyendinaga but also to my grandmother, great grandmother and great, great grandmother. It seems automatic to go to the water they lived on for answers but also, knowing that inside my mom when she was floating softly inside my grandmother, was a little piece that would form my body and spirit. Her essence has touched me. Both are true: my grandmother is my access to the land and community I call home and I feel those lands are my access to her, if I stop and listen. She has already shared all her knowledge with me. Now, I have to listen to remember. I am a part of an individual, familial but also a broader collective remembering happening for a lot of people right now. I am remembering all of the things that were once in my head

photo from You're not here series, 2016

In You’re not here, I am physically returning my body to the Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory but, as I return to my community, so much more is returning. I am placing my grandmother back into the community she never fully got to be a part of. Displacement, uprooting, and relocation have strong connections to my feelings about land as a Mohawk woman. I grew up, and continue to live, on land that is not the original homeland of my ancestors. The land that is now the Tyendinaga reserve is land that continues to be constrained and controlled by the government. You’re not here evokes both the philosophy and practice of colonization and a specific feeling as a mixed-race woman, who often feels invisible while trying to figure out where I belong in a contemporary colonized society. It also evokes for me a longing for the lessons and stories from my maternal grandmother and ancestors that I never got to learn.

video still from Akshótha, 2015

In Akshótha, I create a fictionalized history of growing up with my grandmother. I call upon the matriarchs of my family: using photos of my mom, aunts, grandmother, great grandmother and myself, to stand in for one another. I also play with the idea of history and whose history is acknowledged as truth. Our history books in Canada omit so much of our country's history. I am taking space to rewrite my own history, a powerful and therapeutic undertaking.

video still from Akshótha, 2015

Time spent breathing with water, in relation to the other works, is an exploration of learning from the land because my grandmother was not here to teach me those lessons. Everyone picks a totem for loved ones who have passed away: a photo, a piece of clothing, something that person loved. For me, my grandmother’s totem is water and the land in Tyendinaga. The trees whisper her name, everything all around me holds a piece of her spirit. When I’m saying “keró:roks tsi naho’ténhson sewake’nikonhrhèn:’en”, I am acknowledging that all of the learning is not just for me but for my grandma, as well. We share DNA and so I share her experiences, characteristics and knowledge. Now I can learn and unlearn and remember for her.

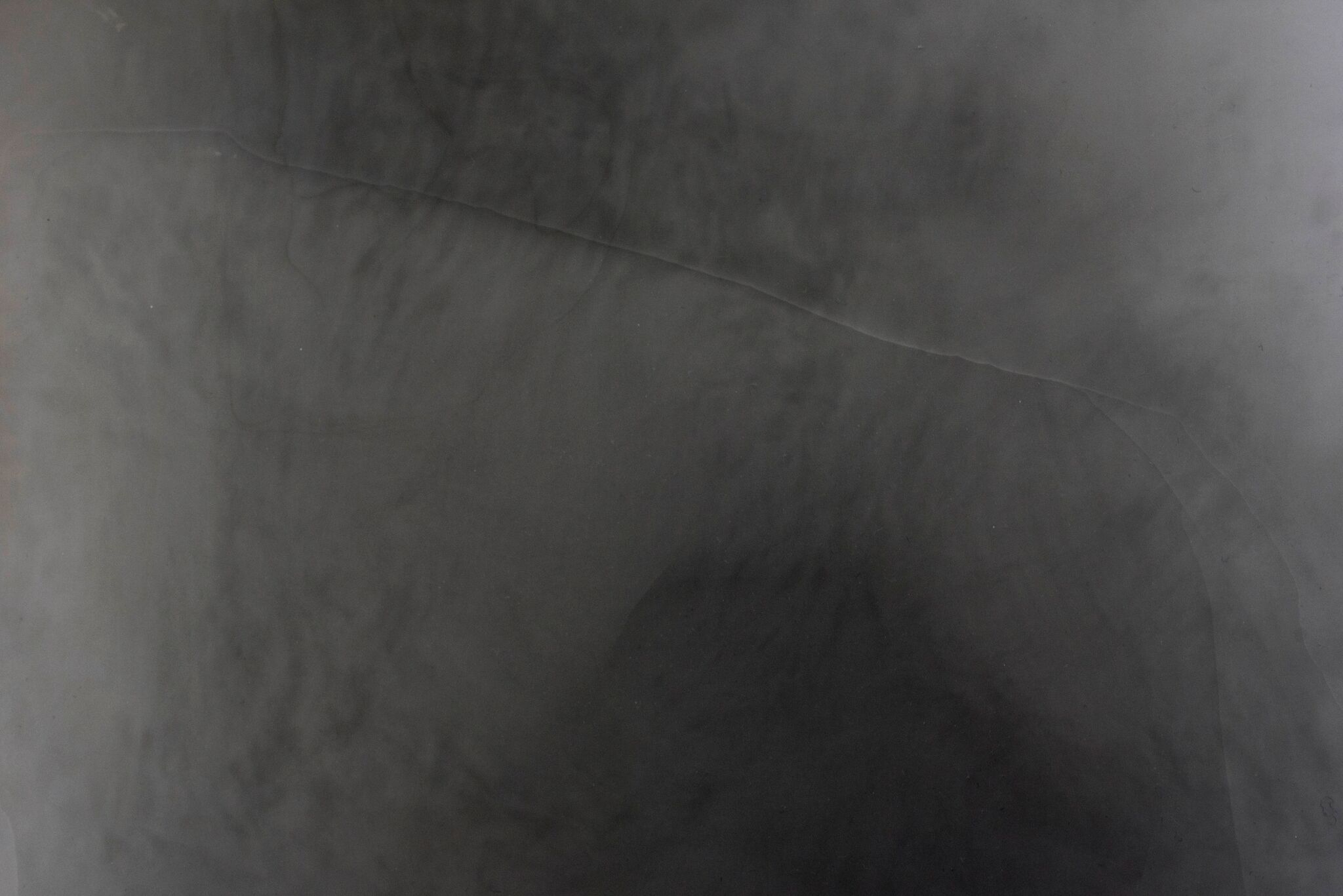

print from Time spent breathing with water, silver gelatin print, 2018

Alysia McMenomy works in her studio in Madoc, finishing the last-minute prepping of bouquets for a wedding on Saturday. Alysia’s company, Begonia Moon, sources flowers and plants from her own garden and local growers to create arrangements and natural beauty products. Alysia's daughter, Olive, stares over the wooden table at her mom as she works. Olive is keenly interested her mom’s work and in the nature around her. Even though she is only 4 years old, she can already name dozens of plants, flowers, rocks, animals.

a fascination with the earth

In a world of disconnection, I want to feel my feet in the sand, I want dirt under my finger nails, I want to smell the soil. Especially in the last few years I have felt this. As someone who works with more and more technology – cameras, social media, emailing clients, I dream of building a garden, playing with flowers and tasting the food I planted weeks earlier. What I have learned since entering college again, is that journalism can be a great tool for asking questions and learning about what you’re interested in. As much as it is seen to be objective, I am drawn, in a selfish pursuit, towards subjects that I want to delve into.

A photojournalist can pretend, for a day, to be a painter, a wood worker, a cook, to remember what it’s like to be a child running through a field. I’ve had this conversation with other photo journalists before. We have a feverous yearning to know what it is like to inhabit bodies and lives that are not ours, to devour life.

I do not find it surprising then, that I am drawn towards those working with their hands and with the earth. I have noticed myself pulled towards florists, gardeners and farmers like a moth to a flame.

Janice Brant pours Bill Wheatley bean seeds onto her hand, one of the over 40 varieties of bean seeds she stores in her home, along with corn, squash, flowers and herbs. Janice is a part of Ratinenhayen:thos, a group who are hoping to open a seed sanctuary and learning centre in Tyendinaga. Janice believes that the Kenh:teke Seed Sanctuary would be important for the community to sustain connection to land and culture, food security, sovereignty and a grounded sacred space for youth, emphasizing that these practices will be lost if the community doesn’t take steps to preserve them.

There is a communion between all people and nature, but I think that women hold a special kindred relationship to our earth. I want to sit at the fire with an elder and listen to her stories about the seeds she’s taken care of, I want to watch a mother teach her daughter about science through the flowers, plants and worms she finds in the yard, I want to watch a floral artist work in her studio creating artwork with lines, colours, textures and shapes of flowers. And I have.

Kristina Steunenberg works on floral arrangements for Valentine’s Day in her home studio in Belleville. Kristina is the owner of Minim Designs which specializes in nature-inspired floral designs for weddings, events, workshops, freelance and editorials. She works with seasonal and locally sourced products to produce bouquets, arrangements and other creations.